A #WorkingOutLoud post today, part of my thought process to understand the fragmented debate around national identity and social justice in the United States. Specifically, i wanted to take time to explore two elements: the notion of flash points, and the narrative of underlying power. I’ll try to contextualise it as this: in the last few days, statues and flags have become flash points of conflict, and individuals with high social status (by which i mean privileged through their role in society, granted to them through formal status, celebrity power, or high authenticity) have started to slug it out in a new structure of power.

Whilst i may refer to the United States, the ideas correlate closely to other evolutions of power and societal shifts we see elsewhere. All national identities are selective stories, written through bloody history, evolving, and disputed. But it’s rare to see the story written so clearly, publicly, and directly, in a stable democracy.

I am unsure if what we are seeing is a conflict within a stable system, or an evolution of the system and notion of nationhood itself. The former maybe comforting to the established structure, the latter may be more likely to be true.

The United States gives a clue in the title (much the same as the ‘United Kingdom’), a title that is both descriptive, was once celebratory, but may now be more aspirational than true. We have seen colonial eras, slavery, civil war, and, more recently, apparently stable systems emerge, but built upon a fractured legacy.

America is not an equal society: disparities of wealth, access to education, quality of education, access to healthcare, and proximity to the New Victorians and the United Emergent Technology Empire of the West Coast, wildly varied and variably distributed. It is a story of difference as much as a story of similarity.

Within this context, flash points emerge. Take the statues of civil war ‘heroes’. Bronze statues are the ways that a country memorialises it’s heritage: they are almost universally contextual, cast by the winners, emotionally laden, and often entirely ignored. You can live in a city your whole life and not be able to name one of the statues that adorn the parks and public spaces. Statues exist as perches for pigeons and aggregators for the empty beer bottles of serenading teenagers. Until they catch fire.

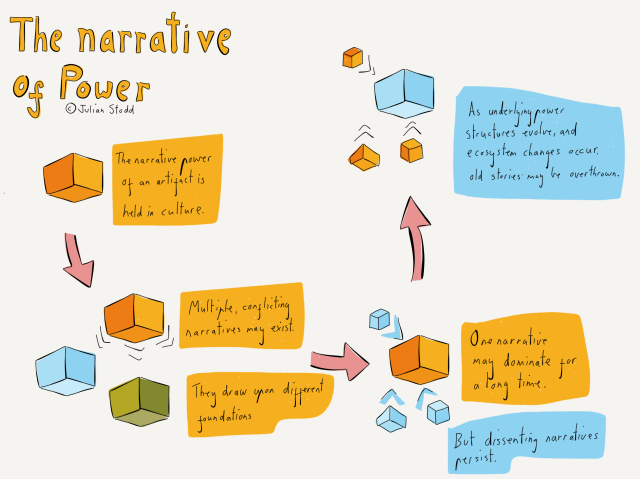

Memorials are not just a thing, they are an idea, an abstracted representation of power, a repression of certain stories, a celebration of others. All culturally associated artefacts have imbued power from context, but the damnable thing about context is that it’s contextual. So the statue that, for years, sat at the heart of a university complex, or in a city park, innocuous and innocent, may suddenly be awarded or bestowed with disproportionate power as part of an evolving national story.

It’s no coincidence that some of the powerful footage of the fall of Saddam Hussein was imagery of his statues being pulled to the ground, decapitated, beaten with shoes, spat upon. Statues represent, codify power. The very notion of ‘bronze’ is culturally associated with memorial and power.

This presents a dilemma: on the one hand, statues are part of our history, part of our story. Expunging, destroying, or removing the, renaming buildings, hiding them away, in some way is to deny history, revise it, or try to rewrite the story. But the problem is this: statues are not neutral artistic symbols of power, they are dynamic repositories of it, and they exist in this fractured and unequal society. To some extent, statues codify and cement the predominant narrative of power, at a time when the narrative of power is being rewritten.

The United States has only had one black president, against a succession of white ones, and has never had a female leader. The UK, which has managed one female Prime Minister had, until recently only one statue of a female figure in Parliament, located, i believe, in a broom cupboard. The power of the past largely dictates the power of the present. In the UK, the landed gentry still carry wealth, and in the US, the white families of oil and industry still carry a great percentage of wealth and establishment power. And through control of the system, perpetuate that power.

It’s a sad but true adage that often white men in a privileged society are proponents of change right up until the point where that change challenges their experience of privilege.

Our cultural artefacts do not simply memorialise history, they actively impose an interpretation of power on the present.

Look at a different angle: i was in Munich this week and, incredibly, saw a tourist goose stepping, laughing as they posed for a camera. Just as statues carry power, so too can movement itself. Ballet is an expression of story through movement, a representation of established power, whilst perhaps break dancing represents more movement from the street, where it is often performed. To perform a nazi salute is illegal in Germany, but not in the United States, where these images have been captured on camera.

Again, it’s the imbued meaning of the symbol that carries the power: a power of association but also, more ominously, a power of intent.

Rewriting history books to remove references to slavery would be censorship, revisionist, and unethical. But statues are not formal histories: they are totemic impositions of power within a contextual structure of power. So removing them may, in some contexts, be appropriate.

Which might take us to a new part of the narrative: how should statues be removed? With chains and hammers, or by curators and conservationists. Should they be melted down, ground up, detonated, or simply moved to museums? Removal can be orderly, or viscerally visual. And, again, each method provides an alternating context.

Removal is a continuation of a current system: destruction is in opposition to it. Vandalising statues, much as the spraying of graffiti, is a claimed voice against the system, claimed with a socially held power, not a formal one.

Museums themselves are interesting: they are a decontextualised space where symbols of power can be stripped of context and meaning. Indeed, sometimes, when we look at prehistoric artefacts, we simply do not know the meaning. It’s lost to us. Whilst the metal and stone have physical characteristics that we can measure, the cultural meaning is held within the culture, it’s tribal knowledge that is easily lost.

If i try to draw this together, i could offer the following narrative: multiple flash points, such as police shootings, statues, flags, salutes, each represent a struggle within a narrative of power. These are not simple matters of discontent within a broadly fair society: they offer a view of an inherently divided one. The backdrop of the Social Age provides the collectivising agency to respond at scale to this inequality: strong social storytellers emerge, social heroes, highly authentic individuals with strong social authority who act as aggregators and amplifiers of the new narrative.

Earlier this week a young lady was killed at a rally, run down by a far right protester: her mother made an impassioned statement, granted high social authority and deep authenticity, through the assault upon her daughter. When it comes to cultural context, the level of power that can be granted to an asset or individual may be almost limitless. Look no further than the ways the varied religions of our societies treat their sacred artefacts: artefacts of power and intent.

We live in uncertain times: the new leaders of our technology companies, and many others, are awarded social power and authority to equal or often exceed our formal leaders. And indeed, in many ways their impact upon our lives is larger. We see movements of dissent against the status quo empowered and enabled at scale by the new levels and mechanisms of social connectivity. And we see established power structures that are often playing substantially by yesterdays rules.

Our cultural landscape will be rewritten around us as the underlying narratives of power evolve. This is why you can now watch ballet in the cinema, buy cheap tickets for the Opera, or see graffiti exhibited in world class galleries. Culture is not owned by the ruling structures, which is why statues are torn down by crowds, not committees. And why sometimes they are smashed, not conserved, because the video of them being smashed itself becomes a cultural artefact.

The Berlin Wall was a formal totem of power and control, the video of teenagers tearing it down with hammers, likewise. And we should not underestimate the sweeping power of the crowd. Within a fractured and fractious history, within a deeply unequal society, the alternative stories of power may easily tear our society apart: i say that not in an alarmist way, but simply as an observation of the one thing we know to be true. All empires fall, no power is eternal, no story that cannot be rewritten and revised.

What is our role in this? If we are not standing up for what is right, we are accepting what is wrong. But we must engage in more than just our similarities: we must engage in our very differences. Reconciliation involves change, but also acceptance of difference. So we must not rewrite our history, but we may need to smash some statues along the way. The leadership we need may come from our formal leaders, but much of it may rest within our communities, because the true narratives of power are fluid and evolutionary, and every voice must have it’s say.

Thanks for your thoughts. I’d like to be alive in 100 years to look back on this century and see what changes have taken place due to climate change and the impact of technology.

Pingback: Inventing Canada… Again | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Government. But By Whom? | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: The Social Revolution | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Types of Power: Manifestations of Control | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Rituals, Artefacts, and the Cohesive Forces of Community | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: #TakeAKnee | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Four Aspects of the Socially Dynamic Organisation | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: A Civil Society? | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Tribes, Communities, and Society: a Reflection on Taxonomy | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Foundational Shifts in Power | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Modes Of Social Organisation: By The People, For The People | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Storytelling Session Ideas #WorkingOutLoud | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Gun Control: a Case Study in Authenticity | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Evolving Knowledge | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Citizen of Apple, State of Lego | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: #WorkingOutLoud o Social Leadership Storytelling Certification | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Building the Socially Dynamic Organisation | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Be More Punk | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Comfortably Uncomfortable | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: ‘Safety Making’ – 9 routes to failure | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Graffiti Story #2 | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: The Social Age 2019: #WorkingOutLoud on the new map | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Guide to the Social Age 2019: Community | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Guide to the Social Age 2019: New Citizenship | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Guide to the Social Age 2019: Power | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Reframing Brexit | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: Reframing Brexit | SDF - Staff Development Forum

Pingback: Fracturing the Narrative | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog

Pingback: #WorkingOutLoud on Communities and Social Movements | Julian Stodd's Learning Blog